At the ominous moment when Russian troops waited on the Ukrainian border days before their invasion, Brittney Griner flew back to Moscow in February for the same reason the best American women’s basketball players spend half the year working in autocracies: because that’s where the money is.

The market for talent lures stars to Russia, where they can command more than $1 million in salary and benefits, 10 times what they have traditionally made in the WNBA. Since 2014, Griner has left the warmth of Phoenix in the WNBA offseason for the cold of Yekaterinburg, a city on the edge of Siberia where the powerhouse team wins championships and pays lavishly.

Being an American women’s basketball player in Russia was good business for many years. That changed instantly when Griner, who had played the first part of her team’s schedule this winter before a break for international play in early February, traveled back to Russia last month.

Griner was arrested at the airport and detained for carrying vape cartridges with hashish oil, according to Russian authorities, who on Saturday said that Griner is the subject of a drug-smuggling investigation that carries a potential 10-year prison sentence.

As her American teammates on UMMC Ekaterinburg were returning to the court, Griner was in custody on foreign soil, becoming entangled in a geopolitical battle.

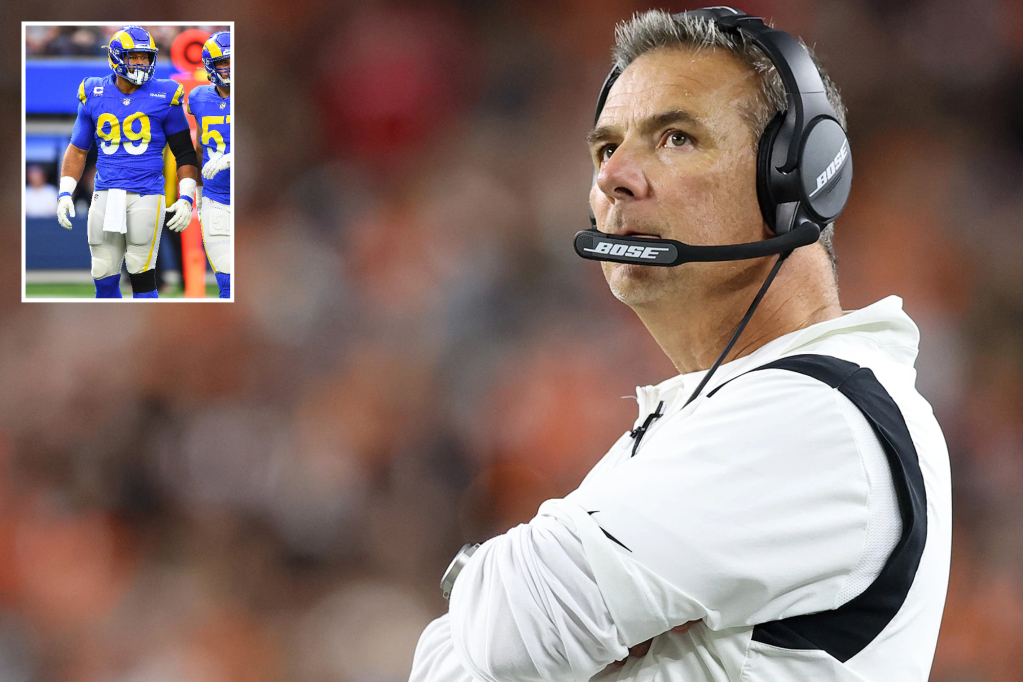

Since 2014, Brittney Griner has been playing with UMMC Ekaterinburg during the WNBA offseason.

Photo:

erdem sahin/Shutterstock

The overseas arrest of a prominent athlete, amid war in Ukraine and the frostiest US-Russia relations in decades, presents a crisis with few precedents.

The recent case of Naama Isaachar, an Israeli-American backpacker who was arrested at the Moscow airport in 2019 traveling with a small amount of marijuana, hints at the complexities of Griner’s situation. Isaachar was sentenced to more than seven years in prison, and was pardoned nine months after his arrest only after a long diplomatic dance between Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu and Russia’s Vladimir Putin.

Days after Griner’s arrest became public, much about her situation remains unclear, including the whereabouts and well-being of a gay, Black woman who is easily recognizable at 6-foot-9. Her representatives and US officials have declined to comment on the specifics of her case.

A review of photos on social media shows that Griner appeared to be in a hotel adjacent to John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York on Feb. 16 wearing the same black hooded sweatshirt that she was seen wearing on video security footage inside Moscow’s airport later released by Russia. An Aeroflot flight left New York at night on Feb. 16 and landed in Moscow on the morning of Feb. 17. UMMC Ekaterinburg’s first game after the international break was Feb. 20.

Griner wasn’t the only WNBA player in Russia during the Ukraine invasion. Her teammates Allie Quigley and Courtney Vandersloot, who are both American, were still in the country and playing for UMMC in late February, as was Jonquel Jones, who was born in the Bahamas. All three appeared in a game on Feb. 23.

On Feb. 27, they played in a domestic game. That same day, the State Department advised US citizens in Russia to consider leaving the country immediately, citing the increasingly limited commercial flight options.

Jones posted on Twitter early March 2 that she had just landed in Turkey. “All I want to do is cry,” she wrote. “That situation was way more stressful than I realized.” Quigley and Vandersloot, who are married to each other, have also left the country.

The State Department issued a fresh warning last Saturday, the day Russian authorities disclosed Griner’s arrest, this time telling US citizens to leave immediately and citing “the potential for harassment” by Moscow security officials.

Griner’s agent Lindsay Kagawa Colas, who also represents Vandersloot, issued a brief statement confirming an effort to get Griner home as part of “an ongoing legal matter,” and declined to comment further. An agent for Quigley and Jones didn’t respond to inquiries. The WNBA has said that Griner has the league’s “full support and our main priority is her swift and safe return to the United States.”

Civilians fled the city of Sumy as Ukraine and Russia agreed on a limited cease-fire there; residents said soldiers ransacked their homes in Irpin; Ukrainian President Zelensky posted defiant video messages. Photo: Emilio Morenatti/Associated Press

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken on Sunday said he couldn’t discuss Griner’s case but that “we have an embassy team that’s working on the cases of other Americans who are detained in Russia. We’re doing everything we can to see to it that their rights are upheld and respected.” The State Department declined to comment further on Monday.

UMMC Ekaterinburg is backed by the zinc and copper riches of the Ural Mining and Metallurgical Company and billionaire owner Andrei Kozitsyn, who has been identified by the US Treasury Department as a business official close to Putin. WNBA teams are bound by a salary cap. Russian oligarchs aren’t.

It isn’t just large salaries that have drawn legends like Diana Taurasi and Sue Bird to the same team in Russia. UMMC’s players typically fly business class, live in luxury apartments and have cars with drivers at their disposal on the team’s dime. They’re also paid on time. Chinese and Turkish teams offer competitive rates, but UMMC tends to get any player they want.

“There’s Ekat, and there’s the rest of the world,” said longtime agent Mike Cound.

Griner, a 31-year-old NCAA and WNBA champion and perennial All-Star center known for her dunking prowess, was one of many Americans in Russia who had to assess their safety over the weeks when Putin publicly weighed military options and basketball paused for FIBA World Cup qualifying.

The international break meant that Griner’s team was off between Feb. 1 and Feb. 20—a critical period of diplomatic negotiating and strategic posturing from world leaders trying to determine whether Putin was bluffing.

UMMC Ekaterinburg players celebrated a victory after a EuroLeague game in January.

Photo:

Vit Simanek/Zuma Press

Jay Field faced the same question. An agent who represents basketball players in the WNBA and international leagues, his team was researching the situation as his clients wondered if it was safe to keep working overseas.

“We encouraged one of our clients not to go back to Russia,” he said. “She made a decision with her family to go back and monitor the situation. If anything occurred, which it did, we would leave as quickly as possible.”

They had strong incentives to keep playing in Russia despite the possibility of an invasion. A standard overseas contract pays on a monthly basis, meaning they wouldn’t be compensated if they decided not to play. They would also be paid in US dollars, not rubles, a measure of financial security to protect them when foreign currencies tank.

A salary of $1 million wouldn’t afford the last player on an NBA bench. But for the WNBA’s best players, it’s both a massive payday and substantial raise. The maximum player salary in the WNBA is $228,094 in 2022, and the minimum for a standard contract is $60,471. Three years ago, before the league’s current labor deal was struck, a top player’s salary was capped at $117,500.

The money is so meaningful that it makes a huge difference in their bank accounts long after stars decide to stop playing overseas. Last year, when Taurasi needed to return home quickly during the WNBA Finals to attend the birth of her child, she reached into her own pocket and chartered a private plane. Taurasi later told ESPN that she was fortunate to have her own means of capital.

“Thank you to my Russian buddies for that,” she said.

The Americans still in Russia found themselves dealing with their own mad scramble to book travel last week, when flights were disappearing as they attempted to purchase seats. Instead of flying back to the US, some escaped through Turkey, since Western airlines canceled flights and much of Europe was closed to Russian airlines.

By then, players were desperate to leave, willing to cover their own expenses, forfeit paychecks and risk potential lawsuits for breach of contract. “You just have to do it,” Cound told his clients. “It’s about safety and getting out of there.”

All WNBA players have now left Russia—except for Griner.

—Evan Gershkovich contributed to this article.

Write to Ben Cohen at ben.cohen@wsj.com and Louise Radnofsky at louise.radnofsky@wsj.com

Copyright ©2022 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

.

0