CNN

—

There are many details we still don’t know about WNBA star Brittney Griner’s arrest in Russia. But there’s a lot we can learn from the experiences of Americans who were detained there in the past.

The country’s strict drug laws also offer some indication of what could be next for Griner, experts say.

Some experts who spoke with CNN were quick to tie Griner’s arrest to the bigger geopolitical picture, and warned she’s likely to be used as a bargaining chip in the days to come. Others say it’s premature to draw any connection between the drug charges Griner’s facing and tensions over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Here’s what experts say are some key things to keep in mind:

Russia’s federal customs agency says a criminal case is underway, and state media reports say Griner is accused of drug smuggling after cannabis oil was allegedly found in her suitcase at a Moscow airport.

Those are serious accusations, given how strict Russia’s drug laws are, says William E. Butler, a professor at Penn State Dickinson Law.

“Russia has, and has had for many decades, a zero tolerance attitude towards narcotic substances, so it’s a serious offense,” he says.

The crime Griner is accused of carries a possible punishment of 5-10 years in prison, Butler says, in addition to the possible imposition of a fine.

But it’s also important to consider another possibility, says Peter Maggs, a law professor at the University of Illinois and an expert on Russia’s civil code.

“There have been a lot of allegations of planting of substances on people, particularly on the part of human rights advocates,” he says.

And a February State Department warning urged Americans to avoid travel to Russia, noting the risk of arrest.

“Russian security services have arrested US citizens on spurious charges, denied them fair and transparent treatment, and have convicted them in secret trials and/or without presenting credible evidence,” the warning said.

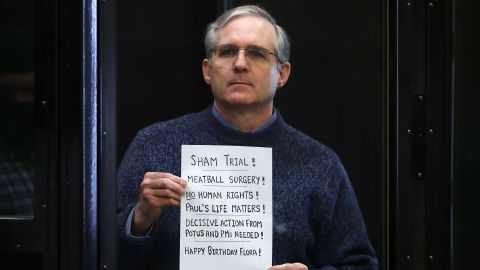

Authorities haven’t said where Griner is being held, and her family has been tight-lipped about the details of the case. But her arrest has brought renewed attention to two other Americans detained in Russia – Paul Whelan and Trevor Reed.

Both men and their families have denied the charges against them and criticized their treatment while in custody.

Whelan, a former US Marine, was detained at a Moscow hotel in 2018 and arrested on espionage charges, which he has consistently denied. He was convicted and sentenced in June 2020 to 16 years in prison in a trial widely denounced as unfair by US officials. In a call with CNN in June, Whelan described the grim conditions of the remote labor camp where he spends his days working in a clothing factory that he called a “sweatshop,” and said, “Getting medical care here is very difficult.”

Reed, a former US Marine detained in Russia since 2019, was sentenced to nine years in prison in July 2020 for endangering the “life and health” of Russian police officers after a night of drinking, according to state-run news agency TASS. US Ambassador to Russia John Sullivan called the trial “theater of the absurd” after Reed’s 2020 sentencing.

In recent calls to his parents from the Russian prison where he’s being held, Reed said he had been coughing up blood, had intermittent fevers and had pain in his chest, according to his father – and the family is concerned he has tuberculosis. In a statement Thursday, Reed’s parents said they were concerned he will be sent to solitary confinement rather than to medical care.

“It’s hard to explain how panicked we are after hearing his voice today,” his parents said.

CNN has reached out to the Russian Federal Penitentiary Service for comment.

Nick Daniloff, an American journalist who was detained in the USSR in 1986, told CNN he has questions about where Griner is being held.

“The Russians seized her and she’s incommunicado. … It’s very possible that she’s being held in the sort of a prison where I was taken – an isolation prison,” Daniloff says.

Daniloff, who was imprisoned for weeks in isolated conditions while officials negotiated his release, says he believes his roommate in prison was tasked with informing authorities about his behavior – and Griner could find herself in a similar situation.

Russian law guarantees Griner access to counsel and consular representatives, Butler says.

“She’s under what I understand to be investigative detention. … She will have had the right to counsel. She will have had the right to contact the embassy, the American consulate, she will have had the right to be visited,” he says.

But a US lawmaker told CNN Thursday that consular officials haven’t been able to meet with Griner.

“The embassy has requested consular access to her … and that has been denied now for three weeks. She has been in touch with her Russian lawyer, and her Russian lawyer has been in touch with her agent and her family back home. So, we do know that she’s OK,” US Rep. Colin Allred, a Texas Democrat, told CNN’s “Don Lemon Tonight.”

“We just know that she’s been held now for three weeks without official government access to her, which really is unusual and extremely concerning,” Allred said.

CNN has reached out to Russian officials regarding Griner’s consular access but has not heard back.

The State Department has declined to provide details on the case, citing privacy considerations.

“We are aware of and closely engaged on this case,” a State Department spokesperson said in a statement Thursday.

This much is clear: the timing is terrible. In the days since Griner’s February detention, Russia has invaded Ukraine, and tensions between Russia and the United States have intensified.

“It’s hard to imagine a more difficult negotiating environment than this,” says Philip Mudd, a CNN counterterrorism analyst who used to work for the CIA. “We have the difficulty of diplomatic negotiations with the Russians, whom we don’t trust, obviously, overlaid with the fact that we’re involved in the war and the Russians don’t trust us. I don’t see how it could be more difficult than this right now.”

The war in Ukraine “makes everything more complex” and will make Russian authorities even more inclined to manipulate the situation, says Nikolay Marinov, a political science professor at the University of Houston.

“They will be less forthcoming, and they will be less cooperative, and it may be a while before they give more official information,” he says.

Authorities haven’t said when, or if, a trial could be held in Griner’s case. Legal experts told CNN a trial could happen quickly, but appeals can be lengthy.

“Usually, where the facts are relatively simple, one would expect things to move very quickly. They’ve got the witnesses of the airport experts, they’ve got the physical evidence, they’ve got the lab report,” Maggs says. “That shouldn’t take a lot of time. But then appeals can take all spells of time.”

He points to the recent case of US businessman Michael Calvey, which concluded more than two years after he was first detained. Calvey was convicted of embarrassment – an accusation he denied.

Despite the serious charges Griner faces, there could still be an “off ramp,” Butler says: Authorities could decide to charge Griner with possession rather than smuggling.

“if they were to decide that she made a mistake, she went through the green line instead of the red line (at the airport), she failed to declare it, they could treat that as an administrative offense instead of a criminal offense,” he says. “If they did that, they wouldn’t charge her with smuggling, they would charge her with … possession. If that were the case, she would be subjected to a fine and probably deportation.”

But Butler stresses there’s a lot we still don’t know about Griner’s case.

“It’s very hard to judge from the outside. … In this case we really know astonishingly little of the actual facts and what’s happened ever since the detention occurred,” Butler says.

At points in the past, when Americans have been detained in Russia and other countries, their release has been negotiated as part of a prisoner swap.

“In my case, the FBI had arrested a Soviet in New York for espionage, and the Russians then arrested me. I was coming to the end of my assignment in Moscow (working for US News and World Report), and … a negotiation eventually took place involving my being released, involving a solution for the guy who was arrested in New York, and there were some other elements that came into play as well,” Daniloff recalls.

At the time, Daniloff credited President Reagan for pushing for his release.

“This was a very complex situation, and if it hadn’t been for President Reagan’s taking a very deep and personal interest in my case, it would probably be some years before I could stand in front of you and say, ‘Thank you, Mr. President,’” Daniloff said at a news conference beside Reagan after his release in 1986.

Could a similar deal be made for Reed, Whelan and Griner?

“The question is whether we have enough to trade for three Americans. But a deal’s a deal, and Putin is going to be ready to make a deal,” Mudd says. “If we do have Russians that he wants, I don’t see why it’s worth avoiding a negotiation just because we’re at war.”

Marinov says Griner’s case is just one small piece in the big geopolitical picture. But there’s no doubt, he says, that Russian officials are contemplating how to use it to their advantage.

“I’m sure they have 10 plans at the moment of how they can exploit this, and what kind of a spin they can put on it – what maximum advantage they can gain,” he says.

Cases like Griner’s have been resolved through negotiation in the past, he says.

But how long that could take in this case, he says, is yet another unanswered question.

0