Rising food prices could lead consumers to expect higher inflation, becoming a self-fulfilling prophesy. Here, a market in Brooklyn, NY, on a recent day.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Text size

The latest increase in consumer prices is worse than it looks, and it may only be the start.

The consumer price index jumped 7.9% in February from a year earlier, hitting a new, 40-year high even before the economic implications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine hit. When you back out food and energy prices, as economists and policy makers like to do since those components can be volatile and noisy, so-called core consumer prices rose 6.4% last month. That is more than three times the central bank’s target meant to represent stable prices.

Excluding food and energy from the CPI seems like exactly the wrong thing to do right now. This week, this column is doing the opposite, stripping out everything but necessary items. Call it the Barron’s Basics CPI, comprising year-over-year changes in foods like meat, eggs, bread, milk, and produce, in addition to shelter, gas, and utilities. The average change in those items climbed 16% in February from a year earlier—and that’s before about a quarter of the world’s wheat exports and a 10th of the world’s oil exports effectively went off-line.

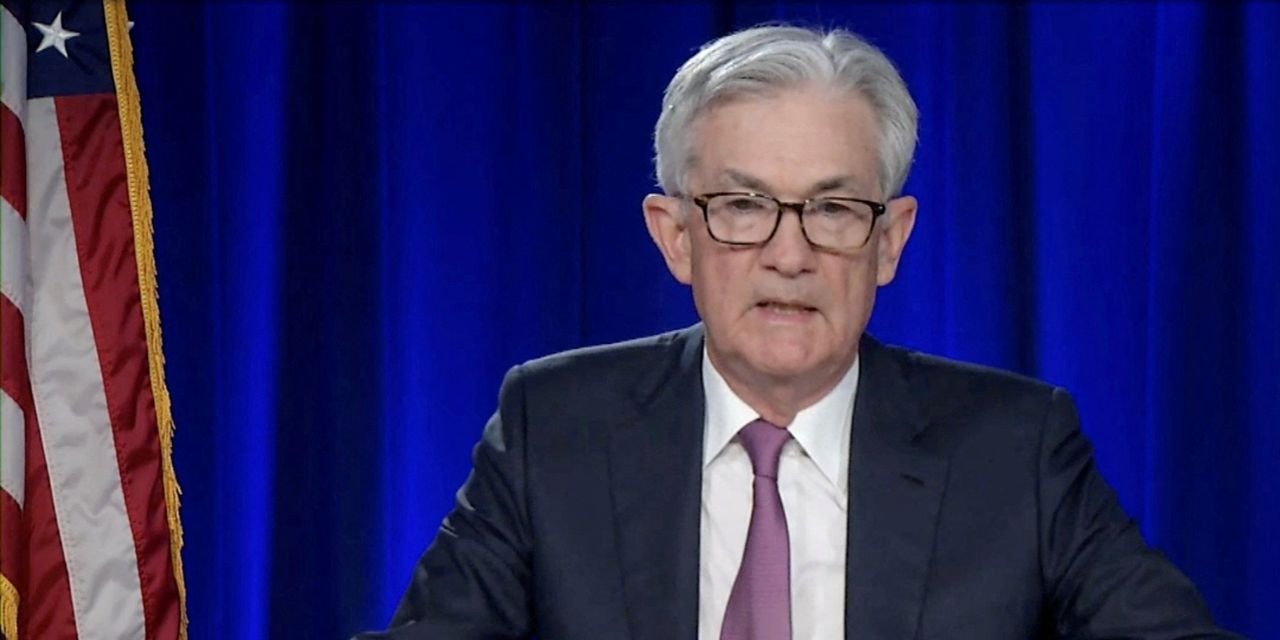

Poll Wall Street economists and you’ll hear that inflation will peak in March, if at a higher level than previously expected. After the latest price data, economists at Deutsche Bank, for example, said headline CPI would top out this month at 8.2% and slow to a 5.1% pace by year end. That would suggest the current geopolitical shock will be a mostly transitory one, to use a word that Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell last year retired.

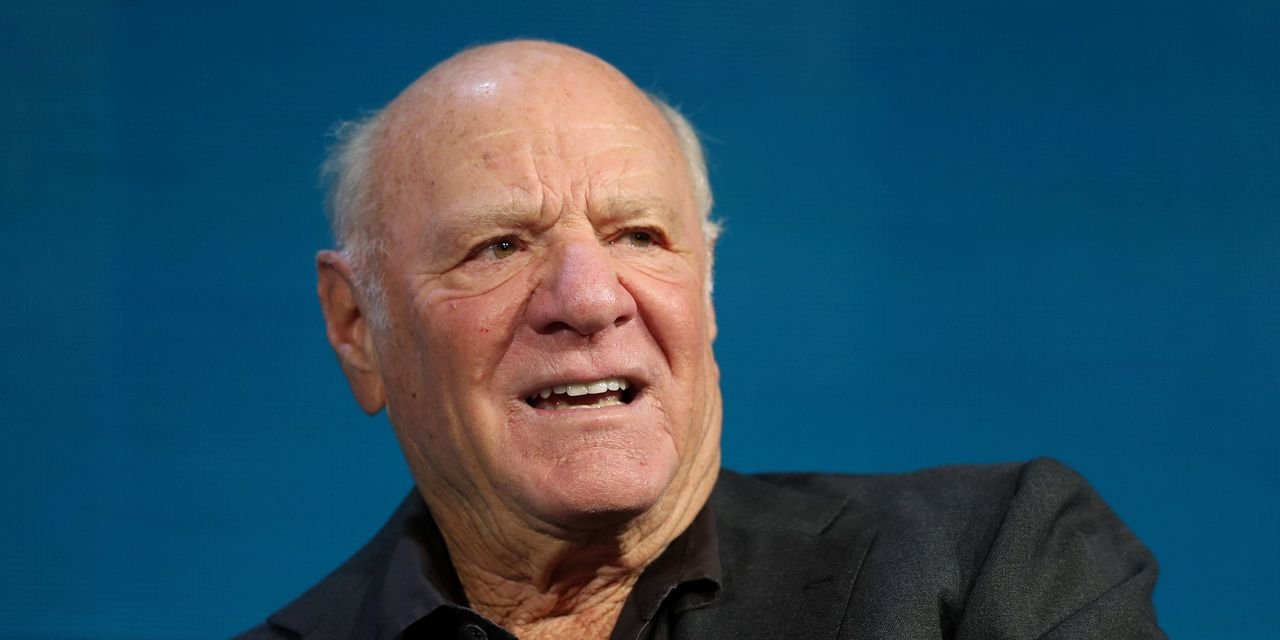

But the conventional wisdom might be discounting the crucial interplay between food prices and inflation expectations. Francesco D’Acunto, a professor at Boston College, says inflation expectations are most heavily influenced by changes in grocery prices. Two months ago, about a fifth of US households said they expected broad price inflation of at least 10%. D’Acunto says that share has shot up to over 60% of households as grocery prices quickly increase. The idea is that if surging food prices have an outsize effect on overall inflation expectations, where stable inflation expectations are vital for stable inflation itself, the odds of unmoored expectations—and thus prices—are rising.

When you consider the idea that the lowest-income quintile of households spend more than a quarter of their income on food, the current environment begins to look more alarming. That is especially true when you consider data from the Census Bureau showing that roughly 10% of American households—and slightly more when looking at families with children—don’t have enough to eat. The latest snapshot predates the war in Ukraine.

The implications of fast-rising food prices go beyond the obvious effects on consumers’ standards of living and ability to drive broad economic growth. Yaneer Bar-Yam, president of the New England Complex Systems Institute, warns that rapid increases in the price of food threaten social systems, with surging food prices the main factor behind major spells of social unrest that are usually attributed to politics. The Food & Agriculture Organization’s Food Price Index is at a record high, with its move reminiscent of the one that preceded the Arab Spring in 2011, says Bar-Yam.

“Food prices are going up so fast. Chances of social unrest are extraordinarily high,” he says. “When a very strong driver of things is changing quickly, we have to understand that the system is becoming unstable,” he adds. That doesn’t mean domestic riots are imminent. But it does highlight the mounting pressure on governments worldwide as already-high food and energy prices ratchet higher in response to sanctions put on Russia.

White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki has said that President Joe Biden would do everything he can to reduce the impact of high prices. But what can Biden, or any politician, reasonably do to immediately affect the prices of basics such as food and fuel? The options to increase energy supply, which in turn affects food prices via packaging and transport, are politically fraught, says D’Acunto of Boston College. The US turning to Iran or Venezuela to fill the void is thorny, and releasing strategic reserves is a card better saved for a potentially more dire situation, he says. That leaves the prospect of more fiscal stimulus, which threatens to exacerbate the very problem it would seek to mitigate.

Ask an economist about hyperinflation and most will swiftly dismiss the idea. That’s understandable, in the context of the term’s classical definition, where the inflation rate exceeds 50% per month. Still, this may be a good time to remember that virtually no Wall Street economist predicted the inflation we have now, even before the current geopolitical shock showed up, with the vast majority of the consensus having espoused transitory inflation.

Hyperinflation is still a low probability, especially if high prices cause the kind of demand destruction that helps trigger recessions. But the odds aren’t zero, says Lawrence Lepard, managing partner at Equity Management Associates. He points to a 31% rise over the past three months in the

iShares S&P GSCI Commodity-Indexed Trust

exchange-traded fund (ticker: GSG), what he calls the best proxy for global commodity prices, in addition to lurching food and shelter costs. Mention “hyperinflation” and you’re written off as a crank and a conspiracy theorist, Lepard says. “But it’s not the joke it used to be.”

It is possible that tighter monetary policy will effectively cool inflation and the geopolitical shock won’t turn out to be as bad as it seems. It is also possible that diminishing purchasing power will push more people back into the workforce, helping to alleviate supply-chain issues and wage pressure, to tamp overall inflation. But it is hard to fully dismiss the many factors at play that carry persistently high price inflation. To be continued…. B

Write to Lisa Beilfuss at lisa.beilfuss@barrons.com

0