The biggest star of Paris fashion week was not in the front row but on the catwalk itself. Cher, pop legend and the new face (and elbow) of Balmain’s new handbag, walked the show finale wearing a silver spandex bodysuit, black platform boots and county-cut cheekbones.

The show took place at the Stade Jean-Bouin in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, chosen for its capacity rather than its location. The audience was made up of nearly 8,000 people, members of creative director Olivier Rousteing’s so-called Balmain Army, who bought tickets by donating to Red. The event was called a festival rather than a show with good reason. They even provided snacks.

Democracy – and food – is not the norm at Paris fashion week where closed doors, front-row champagne and scrabble are the order of the day. But Rousteing’s commercial success – he’s entering his second decade with the label – is largely based on giving people what they want. And this season, that meant over 100 different looks, including dresses woven from straw and raffia, bustiers made from sustainably harvested chestnut bark, blazers emblazoned with Renaissance imagery and more. sure, Dear.

Rousteing’s collection, which veered dizzily from ready-to-wear to couture, responded to her fears of a “dystopian future”, sparked by the recent wave of droughts and forest fires in France. “I’m sure I wasn’t the only one asking fundamental questions about the possible dystopian future that awaits us,” he said. Balmain isn’t a brand known for its shades – the final look was a flame-covered silk dress – but the feeling was there.

Gabriela Hearst, creative director of French brand Chloé, whose legendary client “Chloé girl” will also dress for spring 2023, is a designer well versed in the fight against climate change through her clothes.

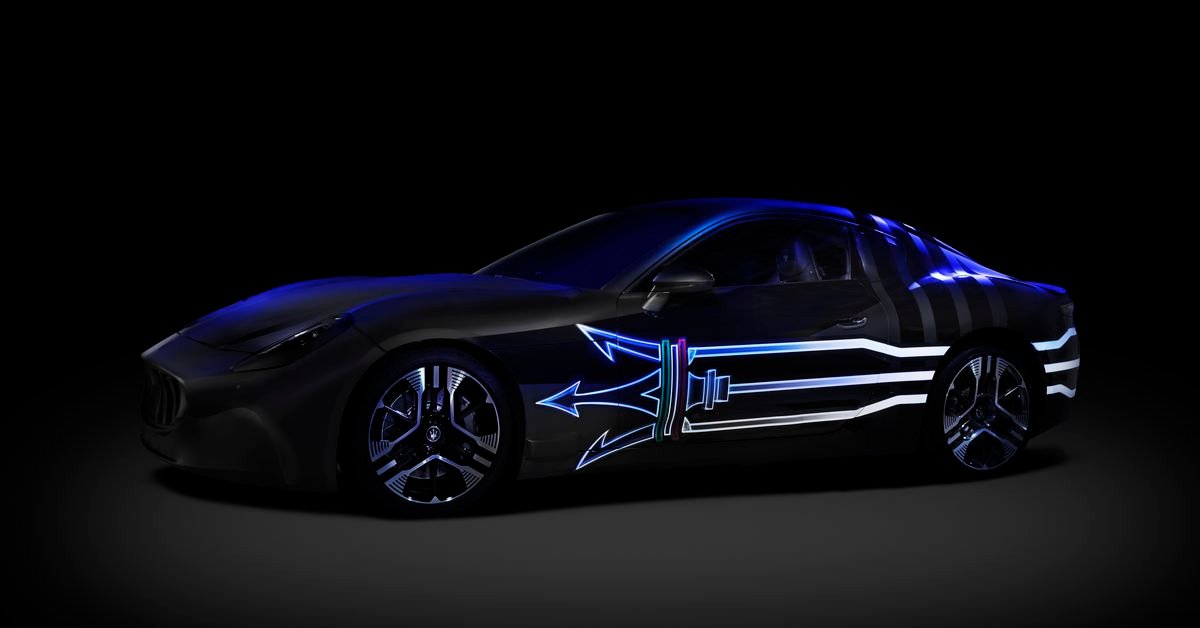

After last season’s “chapter” on rewilding, a relatively mild spectacle that featured melting icebergs on bags and beautiful knitwear, Hearst’s focus shifted to eliminating fossil fuels and fusion energy. This collection was particularly inspired by both the function and form of a tokamak, a complex machine designed to harness the energy of fusion.

On the catwalk itself, the clothes were easier to wear than the tech, with loose-fitting coats and capes in raw silk and linen, finished with flashing hardware closures and you miss. Pants were baggy, suit jackets were bulky, and crocheted dresses skimmed the floor. Proof that the Y2k trend is going nowhere? The rave pants, so called by Hearst in his notes, were finished with eyelets. As in the rest of Paris, there was also a lot of leather – from biker jackets to babydoll dresses to waistcoats. Everything was available in white, black or red, except for a shiny fuschia costume, inspired by the color produced by plasma fusion. As for durability, Hearst’s leather was sourced from French farms and all other materials were 100% traceable.

Showing the collection in the Pavillon Vendôme, a 19th-century event center (and former home of the poet Baudelaire), the staging itself was almost too dystopian. A Tron-style light installation looked impressive, but meant that the clothes could only be seen on half of the catwalk, leaving the audience in the dark at times. Yet, with fashion catching up when it comes to a global understanding of climate change, maybe that was the point.

![“Ghosts” recap: season 2, episode 10 – [Spoiler] To kiss](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Ghosts-recap-season-2-episode-10-Spoiler-To-kiss.jpg)

![The Walking Dead Recap: Season 11, Episode 23 — [Spoiler] Die?!?](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/The-Walking-Dead-Recap-Season-11-Episode-23-—-Spoiler.jpg)

![‘She-Hulk’ Recap: Finale Criticizes MCU Tropes, Introduces [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/She-Hulk-Recap-Finale-Criticizes-MCU-Tropes-Introduces-Spoiler.jpeg)

![‘I mean, I kinda agree [with] them’](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/I-mean-I-kinda-agree-with-them.jpeg)

![TikToker Admits He Lied About Jumping That Tesla to Go Viral [UPDATED]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/TikToker-Admits-He-Lied-About-Jumping-That-Tesla-to-Go.jpg)

![‘Good Trouble’: [Spoiler] Leaving in Season 4](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Good-Trouble-Spoiler-Leaving-in-Season-4.jpg)

![‘The Bachelor’ Recap: Season Finale—Clayton Picks [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Bachelor-Recap-Season-Finale—Clayton-Picks-Spoiler.png)

![‘Upload’ Recap: Season 2 Premiere, Episode 1 — Ingrid Is [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Upload-Recap-Season-2-Premiere-Episode-1-—-Ingrid-Is.jpg)

![[VIDEO] ‘The Masked Singer’ Premiere Recap: Season 7, Episode 1](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/VIDEO-The-Masked-Singer-Premiere-Recap-Season-7-Episode-1.jpg)

![‘The Bachelor’ Recap: Fantasy Suites, Clayton and [Spoiler] break-up](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Bachelor-Recap-Fantasy-Suites-Clayton-and-Spoiler-break-up.png)

0