Washington Post advice columnist Carolyn Hax did not follow the drama of the British royal family. She avoided the Oprah interview, the Netflix documentary series and the explosive excerpts from Prince Harry’s new book. His excuse: “For me, it’s the Kardashians with crowns.

This allows her to see this saga for what it is: the kind of family angst she hears about every day from her readers. When you remove titles, fame and extreme wealth, the crux of all this drama is very ordinary. Tension between in-laws. Power dynamics of longtime siblings. The unbearable weight of family expectations. Who can’t understand?

Our daily Post Reports podcast brought in Carolyn and host Martine Powers to ask some questions (written by producers Jordan-Marie Smith and Sabby Robinson) that were based on painfully real situations, ones royal watchers will surely recognise. And for each, Carolyn offered advice that anyone – not just Harry, Meghan, Charles and William – might find useful.

Here are the best parts of the conversation, edited for length and clarity:

Martine Powers: Carolyn, here’s the first question: “My brother recently published a memoir where he talks at length about our very personal family affairs. And on top of that, he and his wife released a Netflix documentary about our life and our family. I feel like there’s been so much toxic communication between us already. What should I do? Should I speak out publicly or should I try to talk to him to see if we can finally stop this horrible cycle of public shaming? »

Caroline Hax: The first thing that comes to mind is to go to the person. Because if the relationship wasn’t broken, none of this would happen. And I think the way to fix something like that is to take your part in the damage. Why this break? What have you personally done to contribute to this problem?

Powers: It sounds like you’re saying you have to call that person and say, “Look, I did that thing wrong. I will tell you that some of these things were hurtful or that I shouldn’t have done.

Powers: It’s a tough conversation to have.

Hax: Sure. What I see a lot with these relationships that fracture to this degree and for so long and so badly is that there’s usually a difficult conversation that didn’t happen when it should have., because people avoided it or dug in and defended themselves. And instead of just saying, “Okay, you’re right, I’m mad at you. You’ve done a bunch of bad things yourself, but I’m not going anywhere with this until I acknowledge the bad things I’ve done,” people don’t want to do that.

It gets even harder when someone responds to your mistake with an even bigger mistake. And I think a lot of people are tempted to say, “It’s now. What you did was so much worse that it absolved me of everything I did. And that’s not true. You are still responsible for your share, even if it is much smaller.

The relationship may be beyond recovery. It’s always best for you to acknowledge, admit, and apologize for the thing you did wrong, even just for yourself, just because it’s the right thing.

Powers: It sounds like you’re saying that to then, as a hurt person, go out and publish a memoir with all your beef with this person who you know hurt you, that’s a mistake too. Posting memoirs might not be something everyone does, but I think there are a lot of people who, when they’re angry, post something on Facebook about the wrong they’ve done felt by a member of their family.

Hax: If you have an objection to something someone does, you deal with it with the person. If you’re only talking about ordinary people who have something going on in their family, I think telling the world is vanity. Why? Why did you need to tell everyone about it? There must be a reason to bring something public.

If there is an allegation of wrongdoing, [such as accusations of racism], which affects other people or compromises an institution, I think it is important to talk about it. I don’t think other people can say: if you think you’ve been harmed by racist behavior, you have a obligation to talk about it. I think the aggrieved party is the one who can make that calculation. But I think if someone chooses to do it, it’s totally defensible. It is important.

Powers: We have another question: “My husband and I have two young children, and we really want them to have a close relationship with their cousins. But for the past few years, my husband and his brother have had a massive argument, and so our families don’t really see each other anymore. It also doesn’t help that they live in another country. How do I go about explaining to my kids why they haven’t been able to see their cousins and what do I do to make sure they can have some sort of relationship with them in the future ? »

Hax: I’ve received a version of this question a lot, and I find it to be one of the hardest to answer, and here’s why. If you’re cutting a parent, you have to look down the road and recognize that that child of yours could cut you when you do something wrong if you don’t offer them some kind of nuanced understanding of when it’s important to work. about things and when it’s important to protect yourself and cut the tie.

Trying to explain it to a child in childish terms is almost asking too much. So I think you end up with, “It’s an unfortunate situation and we’re not able to see them right now. And I know we love your cousins, and I know they love you,” and you sort of treat him like an unfortunate victim of circumstance. If you don’t burden them with your own biases, then they can pick themselves up when they are in the world.

Powers: The thing that a lot of people struggle with is, should I tell my child why I think his aunt did some really bad things that I don’t agree with and that’s why we don’t talk ? Should they keep it very secret and then let it be a mystery to that child’s whole childhood?

Hax: I don’t think secrecy and mystery prepare your kids to handle things, because as soon as you deny people information, they go looking for it. And they will, anyway. There is the point of inevitability in all of this. But I think if you stick to the truth and what you’ve done with the truth, then in general I think you’re fine. So the truth is that the brothers don’t get along, the two families don’t get along, and that’s really too bad, and I wish it were different, but we won’t see them like we used to. And this is a fundamental fact. It doesn’t throw anyone under the buses.

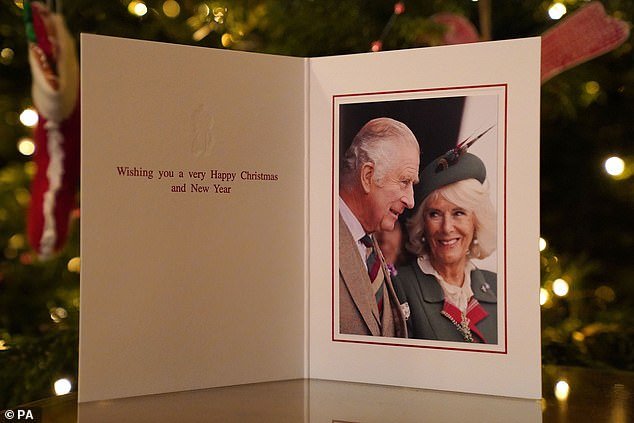

Powers: Okay, so now we have one last question: “So, over two decades ago, I was widowed. When I wanted to remarry the new love of my life – or maybe the longtime love of my life – my sons asked me not to. I did it anyway. But I recently learned how unhappy one of my sons was with my decision to go ahead with this marriage. I love my wife. She’s been a rock by my side, and it hurts me that my son doesn’t see how important she is to me and our family. What do I do now?”

Hax: To live with. You can’t pressure people to change their minds about how they feel, and the more you do, the more rooted they’ll be. The father in this situation must recognize that he misread it and it cost him their relationship. And that goes back to the original answer that we were talking about, where you just own your role for yourself, for your own consciousness. Say, “You know what? I misread this one and I’m so sorry.

You can go on for days about how ‘it was my life to live. I have to make my own choice. I am not going to decide who is going to be my life partner based on my traumatized child. You can say all of these things, and they’ll all be true, but there’s also an emotional truth, and the emotional truth is that it’s going to be a sore point with this kid.

Powers: Do you hear people going through situations like this?

Hax: I can’t think of one that’s directly analogous, but definitely the general idea of someone setting up a condition that’s so cumbersome and complicated. And here’s the problem: If the sons wrote to me saying they want to set this condition, I would tell them no, don’t do this. Don’t prepare for this kind of disappointment. Don’t depend on your father’s choices for your emotional health. Your emotional health depends on you, and the minute you put it in someone else’s hands like that, you’re asking for a lifetime of complications.

![“Ghosts” recap: season 2, episode 10 – [Spoiler] To kiss](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Ghosts-recap-season-2-episode-10-Spoiler-To-kiss.jpg)

![The Walking Dead Recap: Season 11, Episode 23 — [Spoiler] Die?!?](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/The-Walking-Dead-Recap-Season-11-Episode-23-—-Spoiler.jpg)

![‘She-Hulk’ Recap: Finale Criticizes MCU Tropes, Introduces [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/She-Hulk-Recap-Finale-Criticizes-MCU-Tropes-Introduces-Spoiler.jpeg)

![‘I mean, I kinda agree [with] them’](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/I-mean-I-kinda-agree-with-them.jpeg)

![TikToker Admits He Lied About Jumping That Tesla to Go Viral [UPDATED]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/TikToker-Admits-He-Lied-About-Jumping-That-Tesla-to-Go.jpg)

![‘Good Trouble’: [Spoiler] Leaving in Season 4](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Good-Trouble-Spoiler-Leaving-in-Season-4.jpg)

![‘The Bachelor’ Recap: Season Finale—Clayton Picks [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Bachelor-Recap-Season-Finale—Clayton-Picks-Spoiler.png)

![‘Upload’ Recap: Season 2 Premiere, Episode 1 — Ingrid Is [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Upload-Recap-Season-2-Premiere-Episode-1-—-Ingrid-Is.jpg)

![[VIDEO] ‘The Masked Singer’ Premiere Recap: Season 7, Episode 1](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/VIDEO-The-Masked-Singer-Premiere-Recap-Season-7-Episode-1.jpg)

![‘The Bachelor’ Recap: Fantasy Suites, Clayton and [Spoiler] break-up](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Bachelor-Recap-Fantasy-Suites-Clayton-and-Spoiler-break-up.png)

0