Consumer prices in the eurozone rose by a record 7.5 per cent in March from a year ago, piling pressure on the European Central Bank to tighten its ultra-loose monetary policy faster than planned.

The biggest factors driving up eurozone inflation were higher energy and food prices, which have surged since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine hit supplies of oil, gas and other commodities.

The flash estimate for the increase in the harmonized index of consumer prices in March compared with the earlier record of 5.9 per cent set in February and was well above the 6.6 per cent average forecasts of economists polled by Reuters.

The rise in eurozone consumer prices by well above the ECB’s 2 per cent target has prompted some of its policymakers to call for the central bank to cool demand by bringing forward its plan to end net asset purchases and to raise interest rates for the first time in more than a decade.

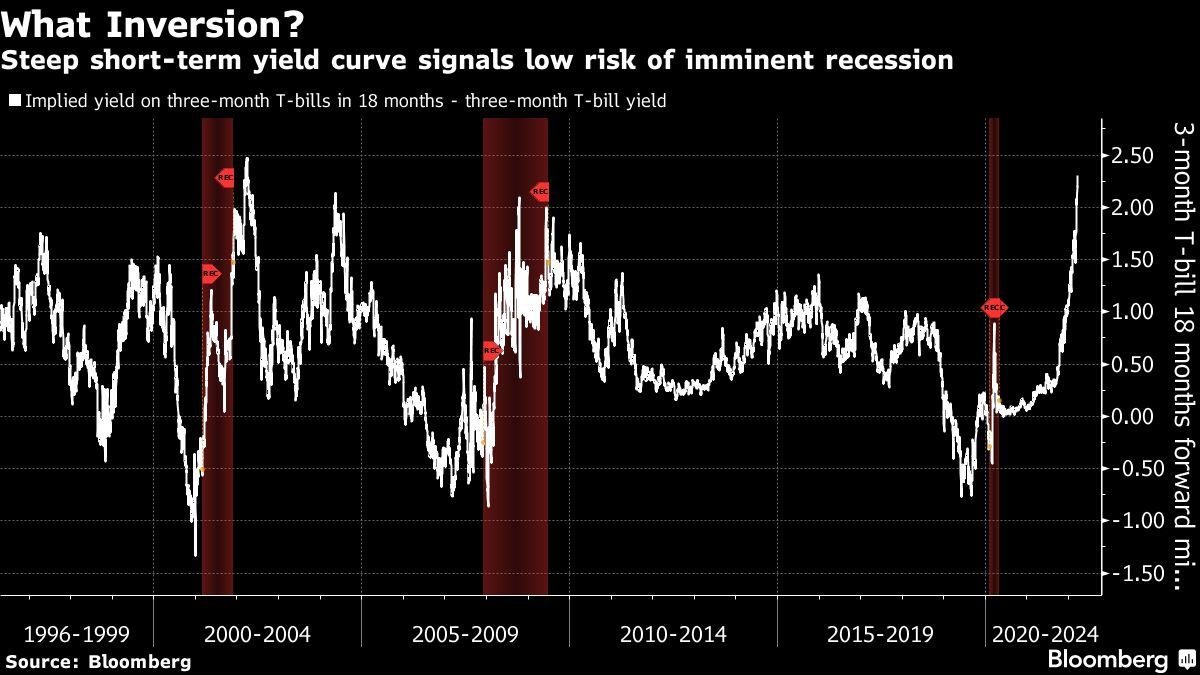

Investors are pricing in 0.63 percentage points of rate rises by the ECB before the end of this year, which would take its main deposit rate back into positive territory for the first time since 2014, up from its current all-time low of minus 0.5 per hundred.

Yet some ECB policymakers worry the war in Ukraine could plunge Europe into recession this year, while the sharp increase in the cost of living could undermine any rebound in consumer demand generated by the lifting of coronavirus restrictions.

“They are being torn in two directions at the ECB,” said Spyros Andreopoulos, senior European economist at BNP Paribas and a former ECB staff member.

“The intention was to exit the emergency policy stance and get out of negative rates this year — and my sense is most people at the ECB would have been on board with that,” said Andreopoulos. “But now they worry the war could have a big impact on growth in the near term, which would delay lift-off to December.”

Several ECB policymakers have said they expect the central bank to raise rates this year and some, such as Klaas Knot of the Netherlands, have said it could do so twice this year.

But the central bank has so far only announced plans to stop net bond purchases by September, when it will decide if inflation will stay strong enough to justify a rate rise. That contrasts with the US Federal Reserve and Bank of England, which have both already started what are expected to be a series of rate rises this year in response to soaring inflation.

“We have opposing forces,” Philip Lane, ECB chief economist, told CNBC on Friday. “We have the energy shock and the prospect of second-round effects pushing up inflation, [while] on the other hand. . . the weakening of feeling [and] the fact that real incomes will suffer from the high energy prices.”

Jack Allen-Reynolds, senior economist at Capital Economics, predicted the ECB would raise rates three times this year by a total of 0.75 percentage points, saying: “The ECB will soon conclude that it can’t wait any longer before starting to raise interest rates.”

In March, energy prices across the euro area rose by an all-time high of 44.7 per cent from a year earlier, while unprocessed food prices advanced 7.8 per cent, Eurostat said on Friday.

Even excluding the more volatile energy, food, alcohol and tobacco prices, core inflation increased from 2.7 per cent in February to 3 per cent in March — underlining how price pressures are becoming more broad-based.

The surge in inflationary pressures was underlined by the 2.5 per cent rise in eurozone consumer prices between February and March, a record month-on-month increase.

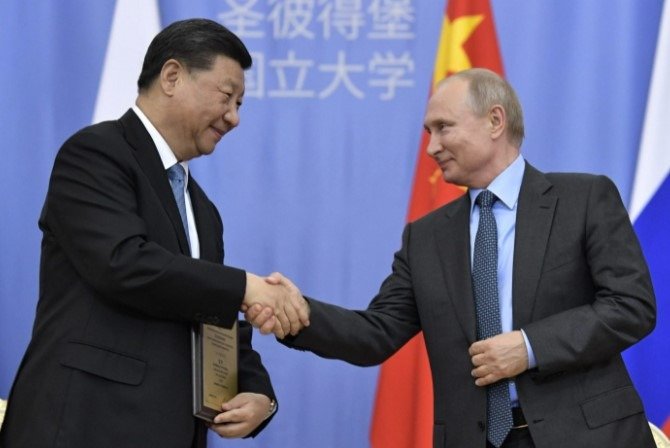

Inflation is expected to continue rising as the Ukraine war adds to turmoil in energy markets and combines with China’s “zero-Covid” lockdowns of key industrial areas to intensify the supply chain problems that are leaving companies short of materials.

Manufacturers in the eurozone reported the biggest price increases for products leaving their factories since such data started to be collected in the 1990s, according to the latest purchasing managers’ survey published by S&P Global on Friday.

![“Ghosts” recap: season 2, episode 10 – [Spoiler] To kiss](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Ghosts-recap-season-2-episode-10-Spoiler-To-kiss.jpg)

![The Walking Dead Recap: Season 11, Episode 23 — [Spoiler] Die?!?](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/The-Walking-Dead-Recap-Season-11-Episode-23-—-Spoiler.jpg)

![‘She-Hulk’ Recap: Finale Criticizes MCU Tropes, Introduces [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/She-Hulk-Recap-Finale-Criticizes-MCU-Tropes-Introduces-Spoiler.jpeg)

![‘I mean, I kinda agree [with] them’](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/I-mean-I-kinda-agree-with-them.jpeg)

![TikToker Admits He Lied About Jumping That Tesla to Go Viral [UPDATED]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/TikToker-Admits-He-Lied-About-Jumping-That-Tesla-to-Go.jpg)

![‘Good Trouble’: [Spoiler] Leaving in Season 4](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Good-Trouble-Spoiler-Leaving-in-Season-4.jpg)

![‘The Bachelor’ Recap: Season Finale—Clayton Picks [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Bachelor-Recap-Season-Finale—Clayton-Picks-Spoiler.png)

![‘Upload’ Recap: Season 2 Premiere, Episode 1 — Ingrid Is [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Upload-Recap-Season-2-Premiere-Episode-1-—-Ingrid-Is.jpg)

![[VIDEO] ‘The Masked Singer’ Premiere Recap: Season 7, Episode 1](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/VIDEO-The-Masked-Singer-Premiere-Recap-Season-7-Episode-1.jpg)

![‘The Bachelor’ Recap: Fantasy Suites, Clayton and [Spoiler] break-up](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Bachelor-Recap-Fantasy-Suites-Clayton-and-Spoiler-break-up.png)

0