To understand why Xiang Guangda is regarded as the Steve Jobs of metals, look at an aerial shot of the Morowali Industrial Park on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. It is here that the Chinese businessman built a vast manufacturing complex that stands as a testament to his domination of the global stainless steel industry.

“Xiang is a visionary,” says Kenny Ives, the former head of nickel trading at Glencore. “Tsingshan’s success in both China and Indonesia over the last 10 to 15 years is extraordinary.”

Yet today the self-made billionaire is in the spotlight for another reason — a huge wrong-way bet that has brought global nickel trading to a halt and plunged the London Metal Exchange into turmoil. On Tuesday, just after 8am, the 145-year-old exchange was forced to stop trading in its benchmark nickel contract after the price more than doubled to over $100,000 a tonne.

At the center of the drama was Xiang and his company Tsingshan Holding Group, the world’s biggest producer of nickel and stainless steel. Over several months the tycoon had amassed a huge bet that the price of nickel would fall, but when the market moved sharply the other way following the invasion of Ukraine he was left exposed to losses of potentially billions of dollars.

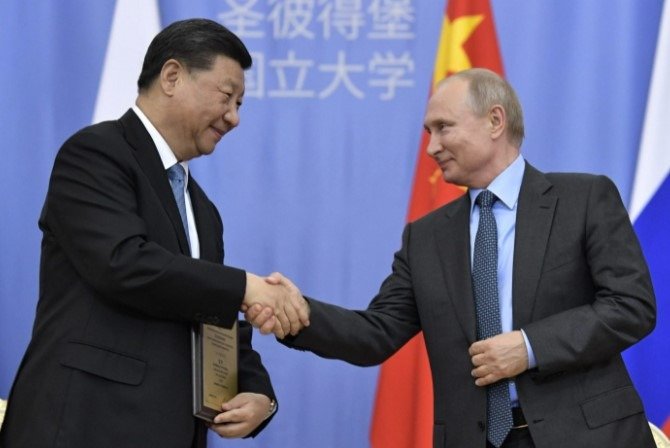

Russia is one of the world’s top suppliers of nickel, which is used to make stainless steel and also in the batteries that power electric vehicles. Traders fear sanctions could disrupt supplies.

Hit with demand for extra cash from his brokers, Xiang was forced to close some of his position by purchasing LME contracts. But his buying only served to further push up prices until the exchange was finally forced to act. Nickel trading remains suspended and it is not clear when it will resume.

“Our positions and operations don’t have any problems,” Xiang told the financial news provider Yicai Global this week. “Tsingshan is an excellent Chinese enterprise.” The company declined to comment for this story.

Yet even as Xiang is sitting on huge paper losses he is not about to give up on his wager, according to people with knowledge of the situation. He has secured credit promises from Chinese and western banks to meet further demands for cash from his brokers and may receive support from Beijing to close his short position

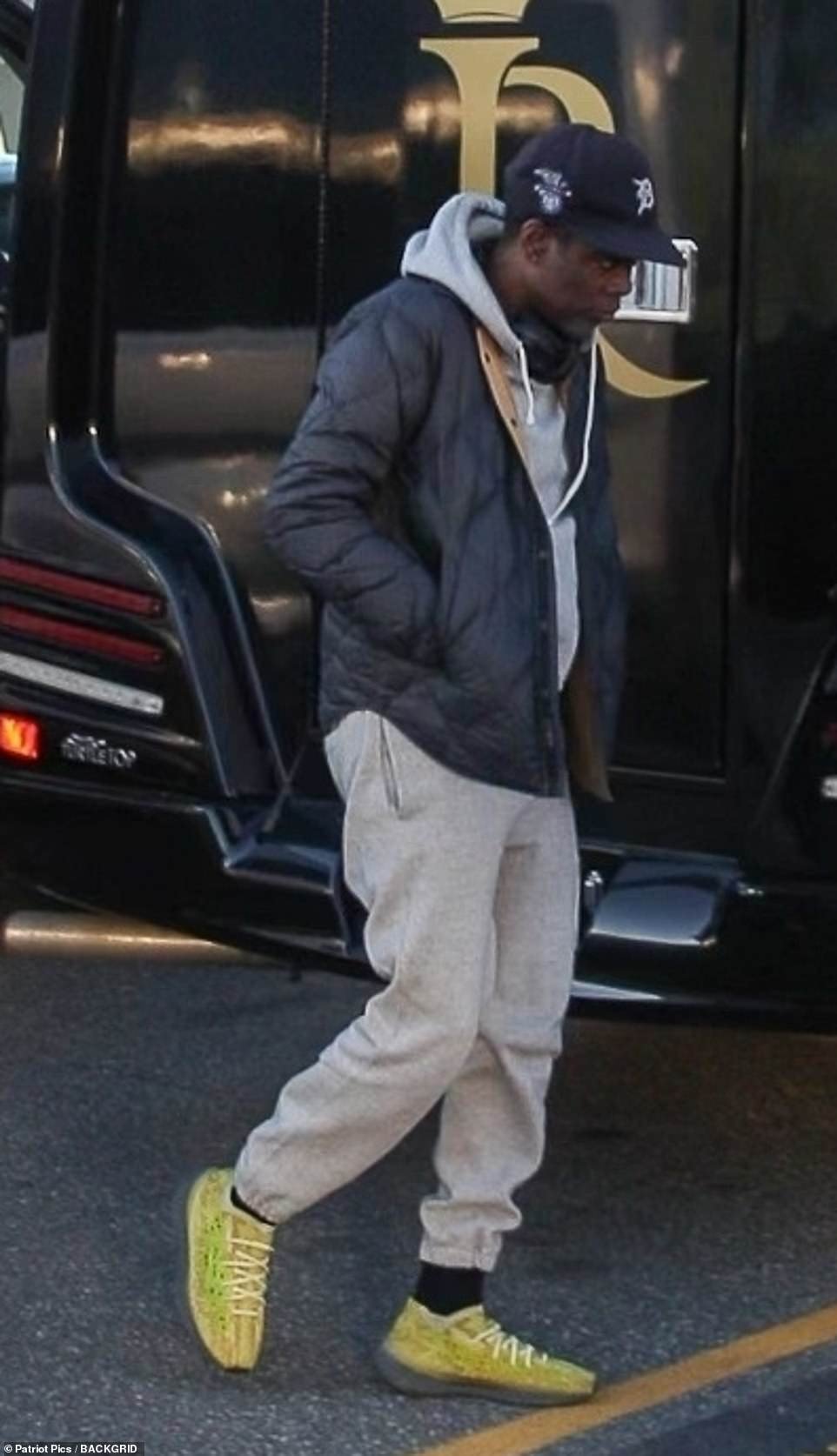

The tycoon who has become known as “Big Shot” was born into a working-class family in Wenzhou, a buzzing city in the coastal Zhejiang province renowned for turning out some of China’s most famous entrepreneurs.

According to Chinese media reports, he got his first job fixing machinery at a state-run fishery, where he was guaranteed work under China’s “iron rice bowl” employment system before Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms. In the late 1980s he joined millions quitting their state jobs to start up businesses — in his case, it was a factory making windows and doors for state automakers that earned him his “first bucket of gold”.

In an interview with a local broadcaster in 2015, Xiang recalled a revelation he had during a business trip to Germany in 1992: BMW and Mercedes-Benz didn’t outsource their doors and windows — they made their own. The factory back home could not last. With the clock ticking, he pivoted to stainless steel, where he saw an opportunity for domestic producers to wean China off its dependence on imported metal.

In a 2020 speech he laid out the reasons for his company’s success: “It’s that Tsingshan hasn’t changed,” he said. “We’re the same now as we were 30 years ago. We wear the same clothes, get out of the same car, and head to the front line.” Xiang himself favors sneakers and button down shirts striped in white and red hues.

Xiang’s family has emerged as one of the most powerful industrial dynasties in Zhejiang, with a sprawling business empire that includes stakes in trade, education and steel companies. Hurun Report, which tracks the wealth of China’s richest individuals, estimates his net worth at about $4.1bn based on his stake in Tsingshan, which employs 75,000 people and has an annual revenue of $40bn, according to Fortune.

“In the mid-2000s they were a small stainless steel producer in Wenzhou. Last year they were responsible for almost a quarter of global production,” says a metals analyst. “They have gone from nothing to by far the biggest player.”

Twice weekly newsletter

Energy is the world’s indispensable business and Energy Source is its newsletter. Every Tuesday and Thursday, direct to your inbox, Energy Source brings you essential news, forward-thinking analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here.

Acquaintances describe Xiang as “unassuming” but “extremely knowledgeable” about his industry. A decision to invest in Indonesia just before the country announced plans to ban exports of nickel-bearing ore in 2014 proved astute. Traders were initially dismissive, saying Xiang had underestimated the risks. But not for the first time he proved them wrong. A good relationship with Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, the army general regarded as the right-hand man of Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo, is said to have smoothed the way.

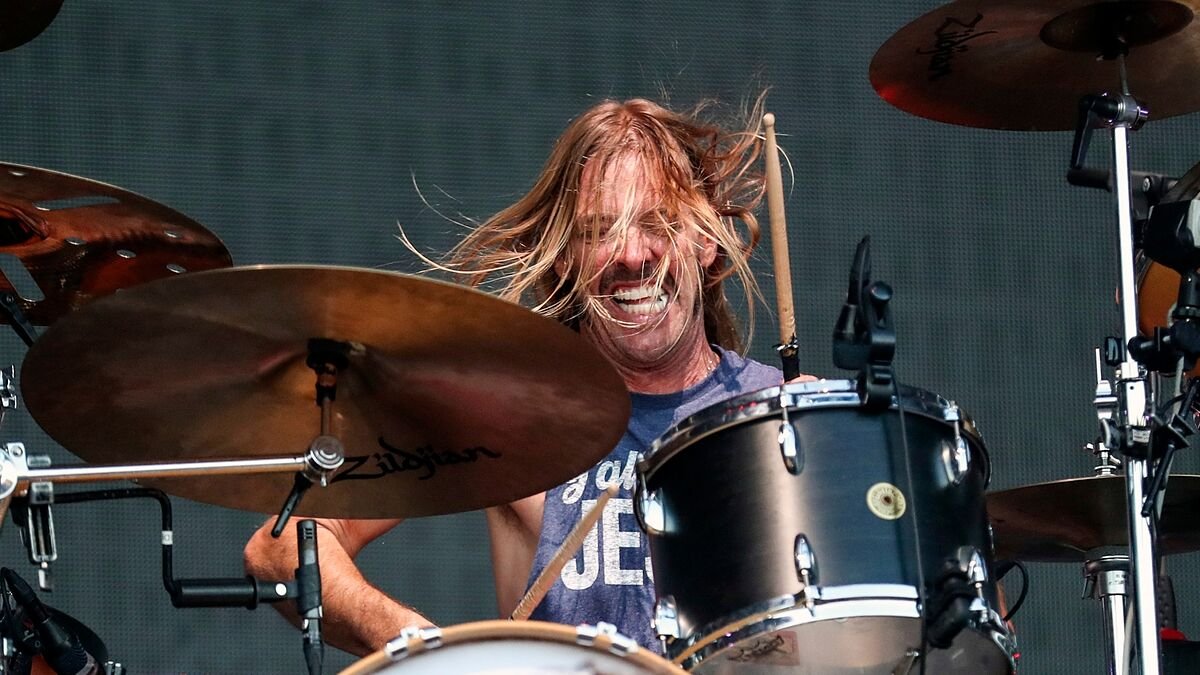

For all his success, Xiang has one weakness, say industry hands: “The guy has an Achilles heel, which you often see among successful people in China: he loves to punt,” said a nickel expert. “I guess he felt that he was the most informed party in the market. . . and wanted to trade on that.”

Despite that, few people are prepared to write him off. “China’s most hardworking people are Wenzhounese,” Xiang said in a 2015. “As long as a person gets exposed to Wenzhou’s hustle culture, he or she will have an impulse to do something.”

neil.hume@ft.com

![“Ghosts” recap: season 2, episode 10 – [Spoiler] To kiss](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Ghosts-recap-season-2-episode-10-Spoiler-To-kiss.jpg)

![The Walking Dead Recap: Season 11, Episode 23 — [Spoiler] Die?!?](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/The-Walking-Dead-Recap-Season-11-Episode-23-—-Spoiler.jpg)

![‘She-Hulk’ Recap: Finale Criticizes MCU Tropes, Introduces [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/She-Hulk-Recap-Finale-Criticizes-MCU-Tropes-Introduces-Spoiler.jpeg)

![‘I mean, I kinda agree [with] them’](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/I-mean-I-kinda-agree-with-them.jpeg)

![TikToker Admits He Lied About Jumping That Tesla to Go Viral [UPDATED]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/TikToker-Admits-He-Lied-About-Jumping-That-Tesla-to-Go.jpg)

![‘Good Trouble’: [Spoiler] Leaving in Season 4](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Good-Trouble-Spoiler-Leaving-in-Season-4.jpg)

![‘The Bachelor’ Recap: Season Finale—Clayton Picks [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Bachelor-Recap-Season-Finale—Clayton-Picks-Spoiler.png)

![‘Upload’ Recap: Season 2 Premiere, Episode 1 — Ingrid Is [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Upload-Recap-Season-2-Premiere-Episode-1-—-Ingrid-Is.jpg)

![[VIDEO] ‘The Masked Singer’ Premiere Recap: Season 7, Episode 1](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/VIDEO-The-Masked-Singer-Premiere-Recap-Season-7-Episode-1.jpg)

![‘The Bachelor’ Recap: Fantasy Suites, Clayton and [Spoiler] break-up](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Bachelor-Recap-Fantasy-Suites-Clayton-and-Spoiler-break-up.png)

0