Covid fatigue is now a widespread affliction. The pandemic has been a lead weight on our way of life for more than two years, and unsurprisingly people no longer want to talk about it. Most of us wish to get on with our lives as if the coronavirus has been vanquished, even though we know in our hearts that it hasn’t. This is how Google Trends searches for Covid-19 have moved since March 2020, in the U.S. and worldwide:

Covid fatigue took two years to set in, and remained prone to sudden spikes of concern. Now, compare that with Google Trends searches for Ukraine, this time over the last 90 days. This chart is for the U.S., but a global chart is identical:

We’ve lost interest in the conflict even though the news continues to be dramatic, and shocking, and even as countries across the world face up to the dilemma over how much to help in arming the Ukrainian military resistance and in isolating Russia from normal economic activity.

Why the loss of interest? Another Google Trends chart offers some clues. Veiled threats from Vladimir Putin that he was prepared to retaliate with nuclear weapons, and the Russian attack on the Zaporizhzhia power plant, stoked once-unthinkable fears of nuclear conflict. Those fears have since dissipated.

Also, the initial perception was that the entire Russian campaign was aimed at capturing Kyiv. With the capital under control, victory in some form would be Moscow’s. As Ukrainian forces repulsed Russian aims to take the city, and Putin’s forces changed their plans and withdrew from positions around it, so concern has dissipated. Here are the results of Google Trends searches for “Kyiv” and “nuclear” over the last 90 days:

If Russia isn’t going to knock out the Ukrainian government altogether, and particularly if we can escape without nuclear war, then, it appears, we think we can safely avert our eyes from the conflict. It’s a distressing and distasteful topic that most of us would prefer to ignore, if we can.

The pattern of sentiment in the population as a whole is borne out perfectly in the markets. After a very brief spike in concern, the upward surge in bond yields continued unabated, while global stocks are now up more than 2% since the eve of the invasion. As Marko Papic of Clocktower Group LP shows in this chart, the number of Ukraine news stories passing through the Bloomberg Terminal has dipped, while investors have continued to sell Treasury bonds despite their traditional role as a geopolitical haven:

The utter insouciance concerning Ukraine news shows up in other asset classes. Eric Robertsen of Standard Chartered PLC offers this graphic to show that the VIX volatility index has returned to its pre-invasion norm, while emerging market stocks, which stand to be most directly affected by the conflict, have recovered almost completely:

Everyone knows that you should “buy when there’s blood in the streets,” but it seems dangerous that so many are comfortable that the worst is known and risk assets are ready to recover.I think the words of Bill Browder need to be taken very seriously here. He is famous as the founder of Hermitage Capital Management, which pioneered investing in post-Soviet Russia, and was forced out of the country and has become an inveterate opponent of Putin. Interviewed by DealBook of the New York Times, he was asked to predict the end game in Ukraine. These are the conclusions of their dialogue:

There is no reasonable way for this thing to end. There’s only an unreasonable way.

It’s either he ends up taking over Ukraine and then moving his way toward the Baltic countries to challenge us at NATO — or for him to be defeated by Ukraine and then having the Russian people overthrow him because he was the weak guy who couldn’t beat Ukraine.

How do you handicap those two options?

I think each of those options has a 15 percent probability.

What’s the remaining 70 percent probability?

That he and the Ukrainians and all of us are stuck in this low simmer. It’s not going to be at the same level of awfulness that it is right now, but at this low simmering conflict that just goes on and on and on for years.

This summation seems reasonable. There are chances of seriously terrible and genuinely positive outcomes. But the likelihood is that this turns into something more like World War I, stuck in a stalemate for years. The attitude in markets seems to be that this can then be safely ignored, much as the grinding conflict in Afghanistan came to be known as the “Forgotten War.”

The problem with this is that Ukraine is in Europe, bordering the European Union, and is a major supplier of raw materials to the rest of the world. This is not like Afghanistan or the many appalling conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa. They might be as bad, or even worse, in human terms. But as far as the investment world is concerned, they have nothing like the same impact.

Further, it’s hard to see how the stalemate can end without the West finding some way to limit its reliance on Russian energy. It will take years, at best. As it stands, energy policy is directly enabling the Russian military campaign. This is particularly clear from the Russian oil price in rubles, as this provocative chart from Matt Gertken, geopolitical analyst of BCA Research Inc., makes clear:

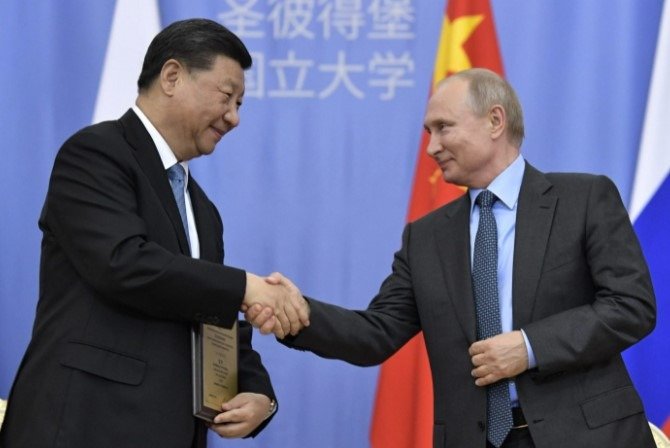

The collapse of the oil price in late 2014 may or may not have been deliberately engineered to make life difficult for Russia, and the current high oil price may or may not have driven Putin’s strategic decisions. But it seems beyond argument that the West needs to find some way to pay much less money to Russia for energy if this conflict is not to drag on and on. Similarly, Russia needs to find alternative buyers to avoid an eventual loss in a years-long war of attrition. That turns the spotlight to India and particularly to China. If they decide to prop up Russia by buying more oil at preferential rates, Beijing will sunder its economic relationship with the EU, and probably usher in a grim return to a bipolar Cold War-like world. Papic of Clocktower puts it as follows:

The fulcrum of multipolarity is not to be found in the bogs and marshes of Ukraine, but in the China-Europe axis. If Beijing continues to side with Russia, it risks creating a bipolar world where two warring camps – the Eurasian Axis (Beijing-Moscow) and the West – do become powerful enough to carve up the planet, leading to the type of a geopolitical forecast that many analysts currently believe is likely: a new Cold War that bifurcates the global economy. As such, what President Xi will do in the next several weeks will not only determine China’s economic future, but also the global distribution of power governing international relations, trade, and finance over the next decade and quite possibly beyond.

We are all already suffering from some degree of Ukraine fatigue. But the temptation to ignore it needs to be resisted. It’s way too soon for that.

What Difference Does It Make?

Having established that markets aren’t according Ukraine the importance it merits, it’s worth looking at the lasting impacts the conflict has had to date. The equity research team at Morgan Stanley found that the companies with the greatest exposure to Europe, and Russia, in each sector tend to have significantly underperformed their peers since Feb. 24. Companies with higher exposure to consumers tended to fare worse:

This suggests that equity investors do see the conflict having an impact, but a localized one rather than any broad geopolitical shifts.

Trade flows, for which data tend to come through with more of a lag, are also showing an impact. S&P Global analyzes South Korean exports as a good global bellwether and finds, as might be expected, that exports to countries in the old Soviet orbit and to the EU have shrunk over the last 12 months. Exports to Southeast Asia have only partially made up for this, tending to confirm the risk of a bipolar world and one with much less trading activity:

The clearest tell that Ukraine is still exerting a major financial impact comes from the foreign exchange world. In a series of zero-sum games, something has to give. So far, the Aussie dollar — the classic commodity currency — has enjoyed sharply better performance compared to the yen and euro, while the dollar has surged to new highs:

This suggests risk aversion and a clear belief that there’s some security in commodities.

How can stocks possibly be surviving so well? If we look at prospective earnings multiples for the U.S. and Europe, they have fallen significantly this year. This is a natural consequence of higher bond yields, but it shows that stocks have stayed so resilient almost entirely because the E in the prospective P/E is still very healthy.

Stocks are resisting the dreadful news from Ukraine because brokers’ analysts are upgrading their forecasts for 2022 earnings despite everything. This week, as the first-quarter earnings season gets under way, will provide new evidence on this. As someone once more or less said, it would be nice if they were right.

The results are in from the French election’s first round, and as expected, Emmanuel Macron will face off against Marine Le Pen in the second. This is a repeat of the runoff in 2017, when Macron prevailed 66% to 34%. The latest polls, however, imply that it will be much closer this time. The Harris-Interactive poll suggests a 51.5% to 48.5% margin for Macron, while a poll for a consortium of French media groups by Elabe shows 51% to 49%. Both are within the margin of error. The two polls are in agreement as to the way this race has developed:

However, the same Elabe poll had Le Pen closing her gap to 25% against 26% for Macron in the first round, while Harris had the gap wider, at 24% to 27%. If Macron’s preliminary results hold up, then at 28.6 % to 24.4% his margin resisted a bit better than the last polls predicted — so maybe the second round polls are also understating his chances. That, combined with a number of defeated candidates exhorting their supporters to vote for Macron in the second round, might explain the initially excited reaction in the foreign exchange market:

That excitement has dissipated at the time of writing, with the euro giving up almost all of its gains as the Asian session progressed. Betting markets saw Macron’s chances of ultimate victory as having improved, but not by much:

Is it reasonable to see Macron’s position as looking a little stronger? It’s unusual for the candidate who finished second in the first round to come back to win, but not unheard of. It happened in 1974, 1981 and 1995, respectively won by Valery Giscard d’Estaing, Francois Mitterrand and Jacques Chirac. And ultimate victors have won despite lower vote shares than Le Pen managed. So this result probably improves the odds of a Macron reelection a little, but it’s hard to say more than that.

Bloomberg’s live blog coverage of the French election can be found here. The numbers I’m offering may have been updated a little, but not by enough to change any market implications. The bottom line is that for the next two weeks, French politics cannot be ignored.

Some more French music is in order. To get you through the next two weeks, Erik Satie’s Gymnopedie No. 1 should be ideal. In a similar serene vein, you could try The Swan from Saint-Seans’s “Carnival of the Animals,” or Ravel’s Pavane Pour une Infante Defunte (performed here in an empty Royal Festival Hall in London during the worst of the pandemic in 2020). For choral works, try Poulenc’s Videntes Stellam, or In Paradisum from Faure’s “Requiem,” or Missa Pange Lingua by Josquin des Prez. For something a little more dramatic, try Pandemonium from Berlioz’s “Damnation of Faust.” It’s how the demons in hell welcome Faust after he’s made his bargain with the devil. Or you could listen to the whole thing. It’s brilliant.

Enjoy the week, everyone.More From Other Writers at Bloomberg Opinion:

• This Earnings Season Will Be Awkward for the Fed: Lisa Abramowicz

• Industrial Anxiety Shifts From Supply to Demand: Brooke Sutherland

• Why the Federal Reserve’s Shrinking Balance Sheet Matters: Mohamed El-Erian

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com/opinion

![“Ghosts” recap: season 2, episode 10 – [Spoiler] To kiss](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Ghosts-recap-season-2-episode-10-Spoiler-To-kiss.jpg)

![The Walking Dead Recap: Season 11, Episode 23 — [Spoiler] Die?!?](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/The-Walking-Dead-Recap-Season-11-Episode-23-—-Spoiler.jpg)

![‘She-Hulk’ Recap: Finale Criticizes MCU Tropes, Introduces [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/She-Hulk-Recap-Finale-Criticizes-MCU-Tropes-Introduces-Spoiler.jpeg)

![‘I mean, I kinda agree [with] them’](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/I-mean-I-kinda-agree-with-them.jpeg)

![TikToker Admits He Lied About Jumping That Tesla to Go Viral [UPDATED]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/TikToker-Admits-He-Lied-About-Jumping-That-Tesla-to-Go.jpg)

![‘Good Trouble’: [Spoiler] Leaving in Season 4](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Good-Trouble-Spoiler-Leaving-in-Season-4.jpg)

![‘The Bachelor’ Recap: Season Finale—Clayton Picks [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Bachelor-Recap-Season-Finale—Clayton-Picks-Spoiler.png)

![‘Upload’ Recap: Season 2 Premiere, Episode 1 — Ingrid Is [Spoiler]](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Upload-Recap-Season-2-Premiere-Episode-1-—-Ingrid-Is.jpg)

![[VIDEO] ‘The Masked Singer’ Premiere Recap: Season 7, Episode 1](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/VIDEO-The-Masked-Singer-Premiere-Recap-Season-7-Episode-1.jpg)

![‘The Bachelor’ Recap: Fantasy Suites, Clayton and [Spoiler] break-up](https://nokiamelodileri.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Bachelor-Recap-Fantasy-Suites-Clayton-and-Spoiler-break-up.png)

0